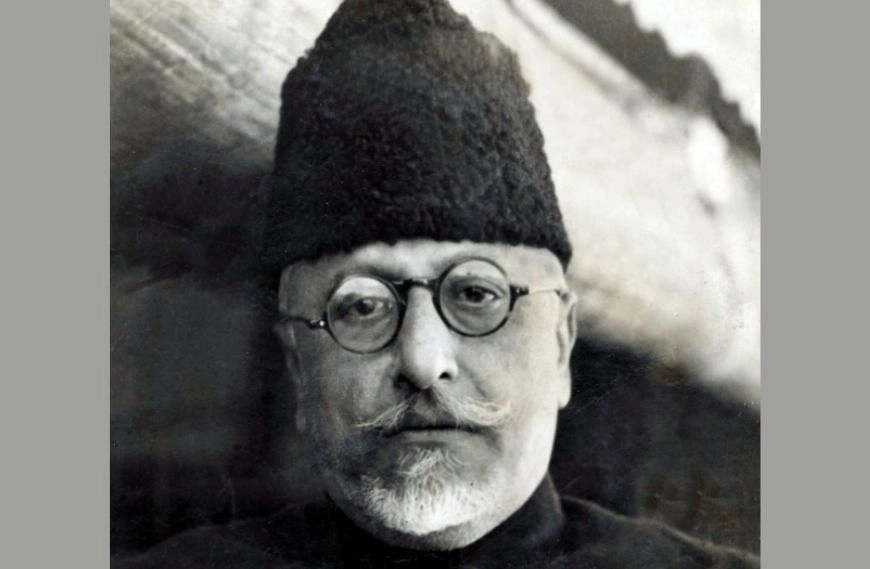

Every year 11 November is celebrated as National Education Day. It marks the birth anniversary of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad. He was India’s first Education Minister and a leading voice in the freedom movement. Most know him as a Congress leader and Gandhi’s ally. Fewer know about the scholar, poet and quiet revolutionary behind the public figure.

Born in Mecca, raised for India

Azad was born on 11 November 1888 in Mecca. At that time Mecca was part of the Ottoman Empire. His family had left India after the Revolt of 1857. They had taken refuge in the holy city. Yet his life would be bound to India’s future.

Roots in Herat and Medina

His forefathers came from Herat in present day Afghanistan. His father, Muhammad Khairuddin, was a noted scholar. He wrote a dozen books and taught thousands of students. His mother, Sheikha Alia, was the daughter of a respected Medina scholar. Knowledge was a family legacy.

A home school like no other

Azad had no formal school. Tutors taught him at home. He learned Arabic first. He then learned Bengali, Hindustani, Persian and English. He studied law, theology, maths, philosophy, history and science. He learned the four madhabs of Islamic law. He grew into a rare blend of faith and reason.

A child prodigy with books not toys

Before he was 12 he ran a library and a reading room. He also led a debating group. He wanted to write on Al Ghazali at a young age. By 14 his articles appeared in respected Urdu journals. At 15 he taught students older than him. By 16 he had completed his traditional studies and started his own magazine.

Married young, driven always

At 13 Azad married Zulaikha Begum. This was common at the time. Marriage did not slow him. It gave him a home from which to pursue learning and politics.

An ink warrior from youth

At 11 he published the poetical journal Nairang e Aalam in Calcutta. At 12 he edited the weekly Al Misbah. He wrote for Makhzan and Ahsanul Akhbar. At 15 he began Lissan-us-Sidq, a monthly he ran despite money troubles. He edited other papers in Amritsar and Calcutta. His pages criticised the Raj and warned against communal division.

Travel that sharpened his politics

At 20 Azad travelled widely. He visited Egypt, Syria, Turkey and France. He met Young Turk leaders and Iranian dissidents. Those trips turned his mind firmly against imperial rule. He embraced full Indian nationalism.

Secret bridges across faiths

Back home he linked with Hindu revolutionaries such as Aurobindo Ghosh. He organised secret meetings in Bengal, Bihar and Bombay. He earned trust across communities. He worked to bind Hindus and Muslims into a single freedom fight.

Papers banned, spirit unbroken

In 1912 he launched the Urdu weekly Al Hilal in Calcutta. It criticised British rule and urged unity. The paper was banned in 1914. He started Al Balagh in 1915. It too was banned. He spent years in jail, including time in Ranchi and Ahmednagar Fort. Bans and jail became part of his story.

Prison as classroom and diary

During 1942 to 1946 he was jailed at Ahmednagar Fort. There he wrote Ghubar-e-Khatir. These were 24 unsent letters to a friend. They explore God, religion and music. They also include more than 500 couplets in Persian and Arabic. In jail he taught Persian and Urdu to fellow prisoners. He played bridge, organised sport and kept a small circle of learning alive.

A builder of institutions

Azad helped found Jamia Millia Islamia in 1920. The college moved from Aligarh to Delhi in 1934 without British aid. As Education Minister from 1947 to 1958 he set up IIT Kharagpur in 1951 and the University Grants Commission in 1953. He pushed for girls’ education and rural schools. His aim was knowledge for all.

Politics with a social conscience

Azad organised the Dharasana Satyagraha in 1931 after Gandhi’s arrest. He argued for socialism within the Congress. He debated strongly with other leaders over the party’s direction. He became Congress president at 35 and served years later from 1940 to 1946. He led from prison and outside it.

A man of many faces on screen

Azad’s life has reached new audiences through film and TV. Actors have brought him to the screen in several productions. These portrayals keep his memory alive for new generations.

Honours, a late recognition

He died of a stroke on 22 February 1958 at the age of 69. The nation honoured him with the Bharat Ratna in 1992. His tomb beside Delhi’s Jama Masjid was restored as a national monument in 2005. In 1989 the Maulana Azad Education Foundation began work to support minority students.

More than a statesman

The well known image of Azad hides the man who loved poetry and long debate. He was a banned journalist, a prison philosopher and a bridge builder between communities. From Mecca to Delhi his life was a journey in search of freedom and learning.

On this National Education Day we remember him not only for the institutions he built. We remember his conviction that true independence grows from education and empathy. Question boldly. Unite deeply. Learn endlessly.

Subscribe Deshwale on YouTube