A groundbreaking fossil discovery from Manipur’s Imphal Valley is reshaping what scientists know about bamboo evolution in Asia. Researchers from the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP) have identified a remarkably preserved 37,000-year-old bamboo stem from the silt-rich deposits of the Chirang River, offering the earliest fossil evidence of thorny bamboo in the continent.

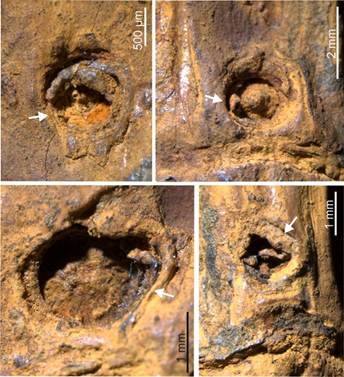

Bamboo fossils are almost impossible to find because the plant’s hollow structure and fibrous tissue decay quickly, leaving behind little or no trace in the geological record. That is why this fossil — preserved with clear thorn scars and bud impressions — is an extraordinary scientific milestone. During routine field surveys, BSIP scientists spotted an unusual stem pattern embedded in the river deposits. Detailed laboratory examinations confirmed it as a species belonging to the genus Chimonobambusa, now named Chimonobambusa manipurensis.

Researchers identified features such as nodes, buds, and rare thorn scars, preserved far better than normally expected from Ice Age flora. Comparisons with modern thorny bamboo species like Bambusa bambos and Chimonobambusa callosa helped scientists reconstruct its defensive structure and ecological behaviour. The presence of thorns indicates that bamboo had already evolved protective mechanisms against herbivores long before modern environments shaped them.

This fossil is not just a botanical revelation — it is a climate story. During the Ice Age, colder and drier global conditions caused bamboo to disappear from many parts of the world, including Europe. Yet this specimen proves that Northeast India served as a climatic refuge where bamboo continued to grow and survive despite harsh global environmental pressures. Warm, humid microclimates in the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot likely shielded species like Chimonobambusa from extinction.

The study highlights the region’s crucial role in preserving life during extreme climate phases. It strengthens the idea that Northeast India acted as a sanctuary for many plant species during glacial periods, allowing them to persist while other regions experienced ecological collapse.

What makes this discovery even more significant is the fossil’s exceptional preservation. Delicate features such as thorn scars almost never fossilize, making their visibility under the microscope a rare scientific gift. The researchers — H. Bhatia, P. Kumari, N.H. Singh, and G. Srivastava — emphasize that this find opens a new chapter in understanding bamboo evolution, Ice Age plant survival, and the deep-time biodiversity of the region.

Published in the journal Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, the study demonstrates how a single fossil can illuminate thousands of years of ecological history. It also reinforces the scientific importance of Northeast India as one of the world’s most resilient biodiversity hotspots.

Subscribe Deshwale on YouTube